In

an article I recently read, Viatcheslav Wlassoff explains that Post-Traumatic

Stress Disorder is triggered by experiencing a traumatic event, such as war

violence, rape, child abuse, or near death experiences, among other experiences.

In cases of PTSD, the emotional wounds linger and it results in symptoms such

as flashbacks of the traumatic event, severe anxiety, hypervigilance, and more.

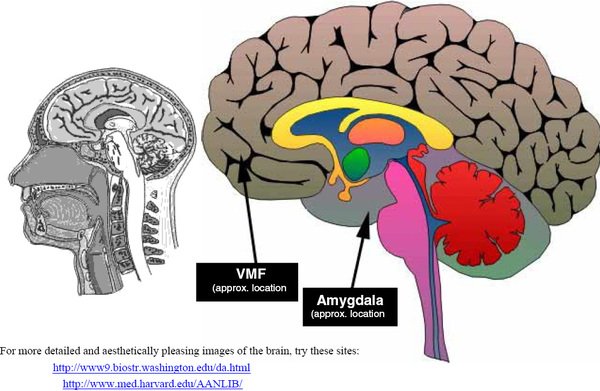

He explains that PTSD actually changes the brain’s structure, namely the

circuit involving the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) and the amygdala.

Neuroimaging

studies have shown that specific parts of that circuit, such as the vmPFC and

the amygdala, differ structurally and functionally in PTSD patients, compared

to healthy individuals. Specifically, in Wlassoff’s article, he explains how in

PTSD, changes in the vmPFC such as reduced volume of the cortex, along with its

decreased function ability, have been shown. He explains that the vmPFC is the

part of the brain that is responsible for regulating the emotional responses

that are triggered by the amygdala.

He

also explains how traumatic experiences appear to increase activity in the

amygdala, and that PTSD patients show hyperactivity in the amygdala in response

to stimuli that are related to their traumatic experiences.

This

prevailing neurocircuitry model explains the stimulus in our environment is

capable of inducing fear by triggering activity in the amygdala, which in turn

triggers the physiological and subjective experience of fear. Neuroscientists have

come to believe that activity in the amygdala is regulated by the vmPFC, and

this has been shown by many studies, such as anatomical tracing studies in

primates that have shown very dense projections from the vmPFC to the amygdala.

Dr.

Michael R. Koenigs, who came to talk at our Neuroscience Seminar this

semester, also described other studies that have also shown how vmPFC activity

is inversely related to amygdala activity, but that this is not necessarily the

case with people suffering from depression. He therefore shed light on the fact

that although the vmPFC is important for coordinating activity across a complex

network including the amygdala, the conventional neurocircuitry model of vmPFC

function is incomplete.

Koenigs

demonstrated this by discussing the findings of several studies. For example,

he studied American combat veterans who fought in the Vietnam War, including

ones with brain damage. Amongst the people he studied with vmPFC damage, he

found that these subjects were actually less likely to suffer from depression.

Furthermore, he discussed another study of a 30 year old woman who suffered

from severe depression for more than 10 years. The woman attempted suicide with

a gunshot to the head, and although she survived, damaged her entire vmPFC.

After the attempt, she showed no signs of depression whatsoever.

These

studies demonstrate that although it is known that vmPFC and amygdala

dysfunction is related to symptoms of PTSD, saying that it it is only these two

factors, and that these work in a causal manner to bring about PTSD symptoms,

would be incorrect. The studies Koenigs discussed have shown that we still have

a lot more research to do to fully understand the neurobiology of psychiatric

disorders such as PTSD.

Works Cited

Wlassoff, Viatcheslav. "How Does Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Change the Brain?." Brain Blogger. N.p., 24 Jan 2015. Web. 06 Dec. 2015. <http://brainblogger.com/2015/01/24/how-does-post-traumatic-stress-disorder-change-the-brain/>.

Koenigs,

Michael. "Revising Neurocircuitry Models of Mood and Anxiety

Disorders Based on Evidence From Brain Lesion Patients and Psychopathic Criminals."

Neuroscience Seminar. Loyola University Chicago, Chicago. 10 Nov. 2015. Speech.

Assignment Help At Sin-compromiso

ReplyDeleteAssignment Help At Tec

Treat Assignment Help

Assignment Help At Ligue-Cancer

Online Assignment Help UK

Geography Assignment Help UK

Economics Assignment Help

TreatAssignmentHelp - An Assignment Writing Company in UK

Treat Assignment Help By GeorgiaStewart

Treat Assignment Help By AnaGibson